I approached Supersymmetry via a car park lift illuminated in a narcotic violet glow. Cellotaped to the lift wall was a piece of A4 paper, upon which was printed ‘THIS LIFT DOES NOT SERVE THE 3rd FLOOR’. Interjected in felt tip between ‘The’ and ‘3rd’ was ‘2nd’. I got in anyway and was served with the 1st as promised, from here I took the stairs to the 3rd and final floor, where I entered the enclosed darkness of Ryoji Ikeda’s latest installation. It is ironically appropriate to enter the digital, dark matter of Ikeda’s Supersymmetry via an out of order lift and a dank walk up the concrete steps of a car park stairwell.

Supersymmmetry presents: ‘ an interpretation of quantum mechanics and quantum information theory from an aesthetic viewpoint […] drawing on [Ikeda’s] exchanges with scientist and engineers […] at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), the worlds largest particle physics laboratory’.

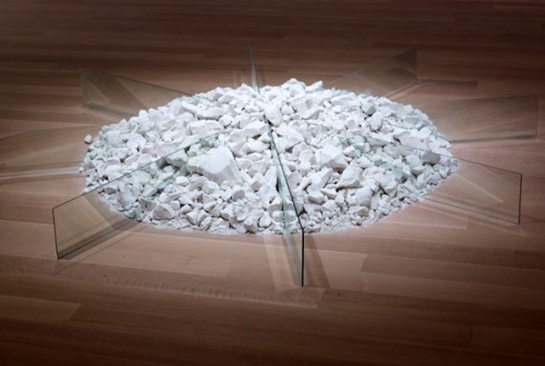

The installation is divided into two separate parts: experiment and experience. Entering the first ‘experiment’ I am enveloped in a visceral bloom of base, intermittently pierced by sublime, frenetic pinpricks of sound. People gather like moths around three, elevated pools of squared and flickering light. Small round particles of matter roll across the surfaces of this illumination, generating patterns of shade, which shift, disperse and congregate. The motion is hypnotic, strangely reminiscent of those oily wave machines, so popular in the 1970’s. These wave machines were the domestic equivalent of the Executive Ball Clickers, whose cradle of steel spheres once provided an aspirational pre-glitch click to the ‘modern’ office soundscape.

From the experiment I proceed through a curtained blackout, toward the noise of experience. Synchronized bursts of light and data travel at speed down a corridor of screens accompanied by an interrupted cacophony of bleeps and blips. The sound suggests organised forms of communication and analysis, as if we were listening to something being questioned, measured and sent. Physically engulfed in the sensual broken waves of digital noise, I am surprised to be suddenly awash in childhood memories of Star Trek; beamed back to the deck of Starship Enterprise, where control panels flash and everything looks like it is doing something, when of course, it isn’t. As I look around I notice that most people are filming, immersed in Supersymmetry through the raised screen of their mobile phone, a gesture reminiscent of Spock, who would survey new worlds with his handheld Tricorder. A sense of pretense begins to intervene in my experience and I am suspicious that the ‘scientific and mathematical model’ that Ikeda presents is a facade, a beautiful, sensual but ultimately empty aesthetic experience.

In a sudden peak of brightness I look up and notice a series of wooden structures attached to the roof: they looked like upside down tables. Above these I can see damp stains of peeling paint. I realise that the structures have been designed to protect the technology of the installation from the holes in the car park roof. These uncomplicated structures offer an eloquent mathematical model for the solution to a real problem: how do we protect the fabrication of Supersymmetry from the reality of rainfall?

From the pavement outside Carroll/Fletcher I stare through a window at A film about a city (2015), part of the new Wood and Harrison exhibition An almost identical copy. The clinical austerity of Wood and Harrison‘s architectural model is touched with elements of futility as I notice hoards of miniature human forms sheltering under the canopy of a square, whilst others sit on a solitary bank of stadium seating, facing nowhere, waiting for nothing to happen. There is something desolate about this city, this idea of a city and I am reminded of the Talking Heads song The Big Country, in which David Byrne describes an aerial view of the perfect country:

I see the school and the houses where the kids are

Places to park by the factories and buildings

Restaurants and bars for later in the evening

Byrne concludes: I wouldn’t live there if you paid me to.

Unlike the ‘scientific and mathematical models’ of Ikeda, these models, reminiscent of train sets and Airfix kits, are intimate human spaces, they share a physical ratio with reality.

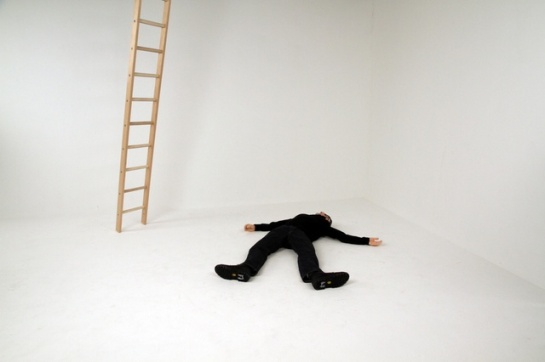

In the video installation 100 falls (2013), Harrison climbs a ladder ascending out of frame. A pause. And then a human dummy dressed as Harrison, drops to the floor. An obvious video edit and the lifeless dummy reanimates as Harrison. He stands up and proceeds to climb the ladder again. So it continues, one hundred times and then, one hundred more. As I talk to one of the Gallery administrators I am aware that behind his back, whilst we chat, Harrison continues with his pathetic ascent and fall, caught in a tragic, inevitable loop of self-harm. The sense of inevitability continues in Semi Automatic Painting Machine (2013) in which we observe various objects as they are mechanically conveyed through a process of being spray-painted. Amongst the bunting, plants and flip charts, we find John Wood, who was born with a face that looks like it has always been expecting this to happen. He is transported and sprayed white, turned, conveyed and sprayed high visibility yellow. Just as Harrison accepts the inevitability of his continual fall, so Wood is resigned to his place in the chromatic production line of the painting machine.

The downstairs gallery seems abandoned, models of tennis courts and industrial estates are deserted; the funfair has moved on. In the out of town car park of the video installation DIYVBIED (Do-It-Yourself, Vehicle Bourne Improvised Explosive Device), model cars randomly explode, not in a CGI altered reality sort of way, but in an indoor firework, Captain Scarlet sort of way. The cars look out of date, unexciting variations of the Hillman Avenger or Morris Marina (once the most popular car in the UK). As one car explodes and then another, I am reminded of those television images of motionless cityscapes, evacuated in response to telephone warnings and suspicious devices, scenes which are then suddenly reanimated by a controlled and remote explosion. As another door flies off another Avenger, every car becomes suspect and the anachronistic image becomes a contemporary premonition of landscapes to come.

As with all of Wood and Harrison’s work there is an obsessive attention to detail. In the gallery upstairs their almost compulsive obsession to order, results in a series of small, pointless and joyous interventions. In what appears to be the office work of bored and idle hands, drawing pins are organised, pencils sharpened, rulers bent and string measured, In the senseless world of Wood and Harrison, everyday objects are faintly rearranged and organised into poetic models, which question our perception of the tangible and concrete, perhaps much more than the aesthetic particle physics and sensuous digital immersion of Ikeda’s Supersymmetry.