Water is a mysterious element […] it can convey movement and a sense of change and flux. Maybe it has subconscious echoes — perhaps my love of water arises from some atavistic memory of some ancestral transmigration.

Andrei Tarkovsky

I was recently invited to contribute to If Wet at the Flatpack Festival in Birmingham. Devised and organised by Sam Underwood and David Morton, If Wet normally takes place in Callow End, Village Hall and is ‘part test bed, part salon; a place for artists to showcase their latest sonic works and research’. It is not an event exclusively concerned with wetness, its title coming from the traditional English retreat indoors in response to a sudden downpour. However, for this urban excursion, If Wet focused (eponymously) upon the sound of water, bringing together a babble of soggy voices. Beginning with a short history of MortonUnderwood’s “water instrument” and included a gorgeous and possibly erudite recital upon said instrument. I say possibly erudite because, as a new instrument, a definitive method of playing is still to be discovered and the full vocabulary of its wetness yet to be heard. Prof Trevor Cox introduced some awe inspiring acoustics from his Sonic Wonderland, instruments and spaces, which operate at the intersection of human endeavor and natural phenomena: from the disconsolate (Tom Waits) moan of a Wave Organ to the longest reverberation in the world, formed in the vast emptiness of Inchindown oil storage tank, Scotland. For my own part I chose to consider and discuss the relationship between sound, memory and water using three of my dampest works: four walks around a year, ˈtʃɔːk: eight studies of hearing loss and the installation rain choir.

In his book The Strange Familiar and Forgotten Israel Rosenfield questions the idea of memory as a fixed system of storage and retrieval. Proffering a dynamic model, Rosenfield writes:‘We understand the present through the past, an understanding that revises, alters and reworks the very nature of the past in an on-going, dynamic process’.

Sound too is dynamic; a space ‘without fixed boundaries…[auditory space] is always in flux, creating its own dimensions moment by moment’. Water shares this state of flux, just as sound is coloured and formed by the present situation of its audition, water borrows its form from its current place of occupation. For Gaston Bachelard the substance of water is ‘full of reminiscence and prescient reveries’. Metaphorically we also lend the substance of water to memory; our memories have fathomless depth, they sink, submerge and rise to the surface of consciousness.

Four walks around a year: winter, the final perambulation of a soundwalk quartet through the wet-lands of the winnall moors reserve in Winchester (UK), begins with an archive recording of city residents remembering the flooding of the moors in the years before and after ‘this last war’. These voices, which flood the landscape with history, emerge and submerge beneath the crisp, slowly thawing soundscape of winter. That which was then solid now melts, the sound dissolving not only the landscape, but substance itself.

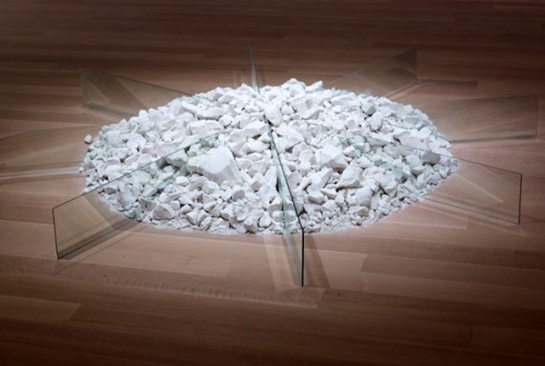

Chalk (mirror) dissolve: after Robert Smithson

As part of If Wet, I performed a live dissolve, immersing various fossils and fragments of chalk (microbiological fossils) in vinegar. This process of sublimation, explored in ˈtʃɔːk: eight studies of hearing loss, makes audible a flight from substance, as the effervescent pre-historic CO2 escapes back into the present air: like a breath held in matter for millions of years, now quietly exhaled. One of the chalk fragments dissolved was ‘borrowed’ from an incarnation of Robert Smithson’s Chalk Mirror Displacement (1968). This was not intended as an attack on art history, but rather a sympathetic homage to Smithson’s occasionally visible Spiral Jetty. In counterpoint to this sublimation of matter, Trevor Cox, acoustic engineer and author of Sonic Wonderland, introduced us to the Great Stalacpipe Organ in the Luray Caverns, Virginia, whose ‘pipes’ have slowly dripped into solidity and stone: a precipitation into (sonorous) form.

A ghost of previous rain: recomposed version of the rain choir for If Wet

The sound of rain evokes a strange sense of isolation and reverie. In the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, its acoustic (and visual) presence quietly soaks the viewer in a sensual intimacy full of reminiscence and memory. As a wet conclusion to my talk I composed my own ghost of previous rain. Based on recordings of and from my site-specific sound installation rain choir, exhibited last year in the crypt of Winchester Cathedral, this acoustic shower mixed the drip drep and drop of gutter recordings with the live dissolve of limestone fragments taken from the walls of the crypt. Water can dissolve and dissipate, but it may also combine and associate. In his autobiography of sight-loss, Touching the Rock, John M. Hull describes how the sound of rain: ‘has a way of bringing out the contours of everything; it throws a coloured blanket over previously invisible things [and] creates continuity of acoustic experience […] The rain gives a sense of perspective and of the actual relationships of one part of the world to another.’

Yet this ‘perspective’ remains acoustic, in that it is fluid and dynamic, place emerging and disappearing in sonic detail, ‘moment by moment’ without the concrete solidity of visual form. In his book Water and Dreams, Gaston Bachelard recognises this ability of water to simultaneously dissolve and unite: ‘The first to be dissolved is a landscape in the rain; lines and forms melt away. But little by little the whole world is brought together again in its water. A single matter has taken over everything. “Everything is dissolved.”’

Just as the sound of CO2 escaping from a dissolving fragment of chalk, quietly announces the immanence of nothing in everything, so too the sound of rain remembers the ‘substantial nothingness’ of water. For John Hull, listening to the rainfall, extinguishes the borders between himself and the wet landscape, as if each raindrop were falling in his brain, he becomes one with the rainfall, a drop of rain at once present and disparate, substantial and not.

O soul, be chang’d into little water-drops,

And fall into the Ocean – ne’er be found