‘[The Tractatus] exists in two parts’, wrote Wittgenstein, ‘the one presented here plus all that I have not written. And it is precisely this second part that is the important one. […] I’ve managed in my book to put everything firmly into place by being silent about it’.

Extract from introduction to: Saying Nothing to Say: Sense, Silence and Impossible Texts in the 20th Century.

In May I was invited to present a paper at, Saying Nothing to Say: Sense, Silence and Impossible Texts in the 20th Century; an interdisciplinary conference, supported by the Humanities Research Centre and organised by Tabina Iqbal at the University of Warwick. Bringing together speakers from literature, philosophy, art history and photography, the conference ‘trace[d] the contexts, conflicts, and legacies of Wittgenstein’s claim:

“In art it is hard to say anything as good as: saying nothing.”’ (ibid)

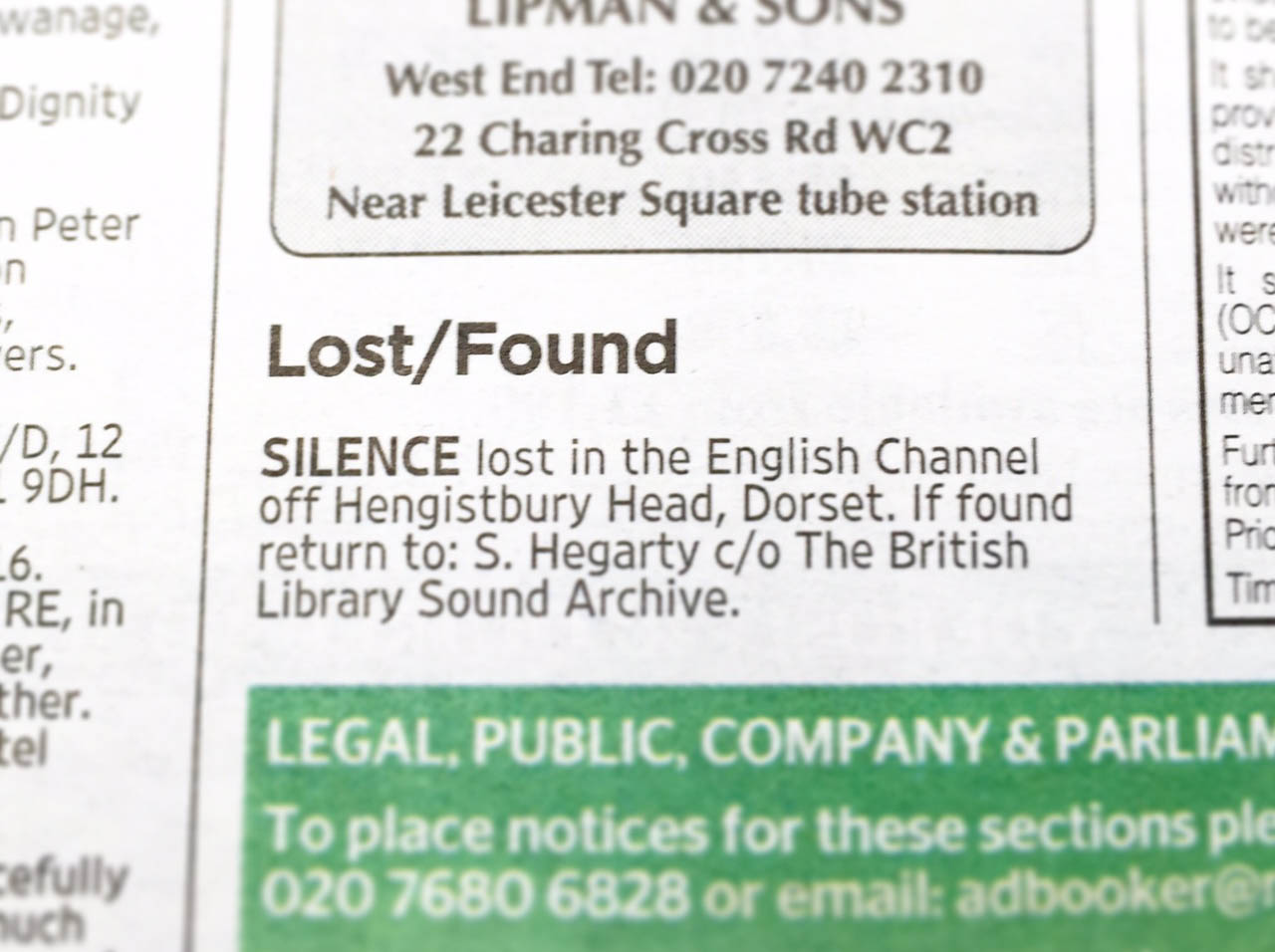

Images: Silence on Loan | Silent [tyre] print | Silence Lost:North Sea (Times Announcement)

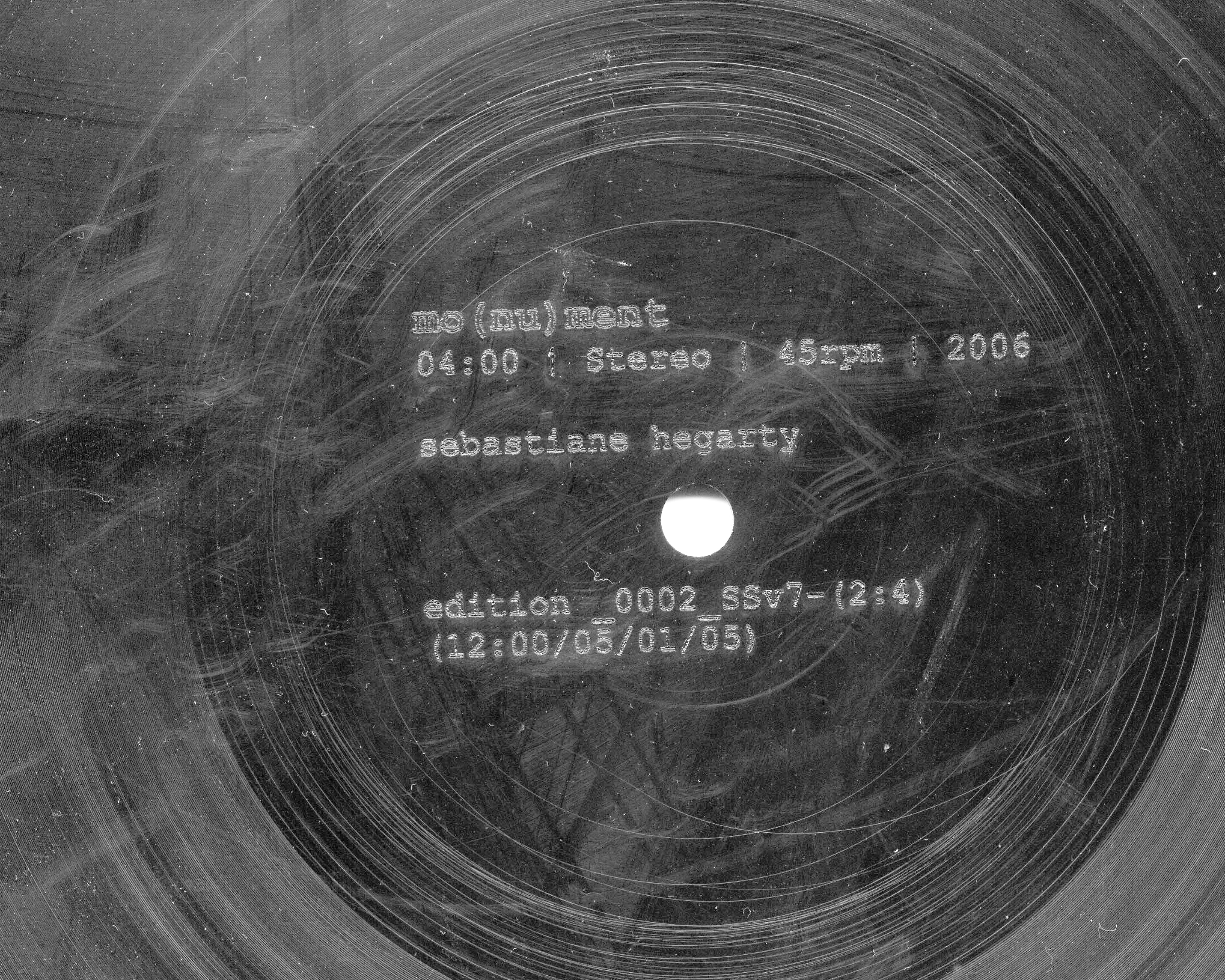

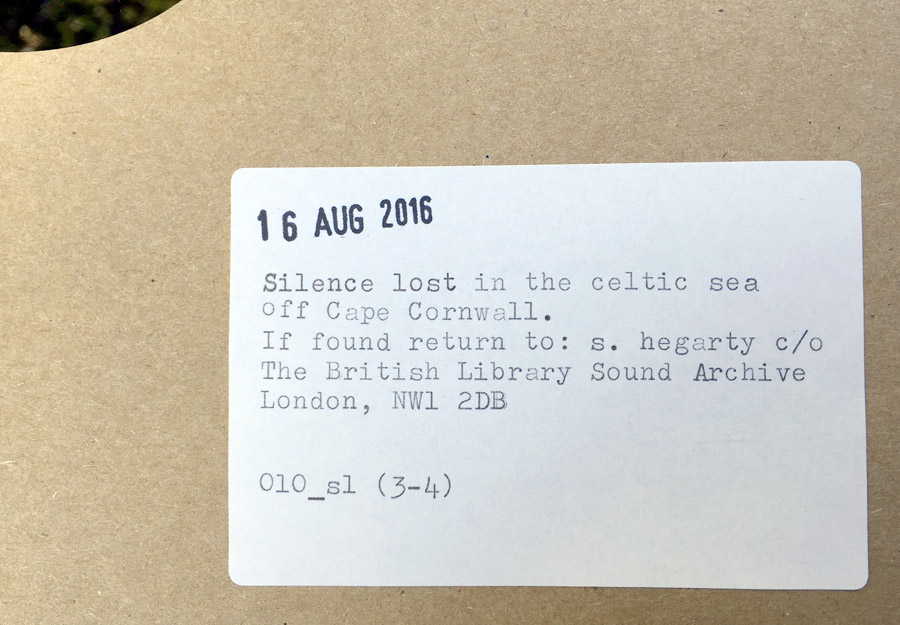

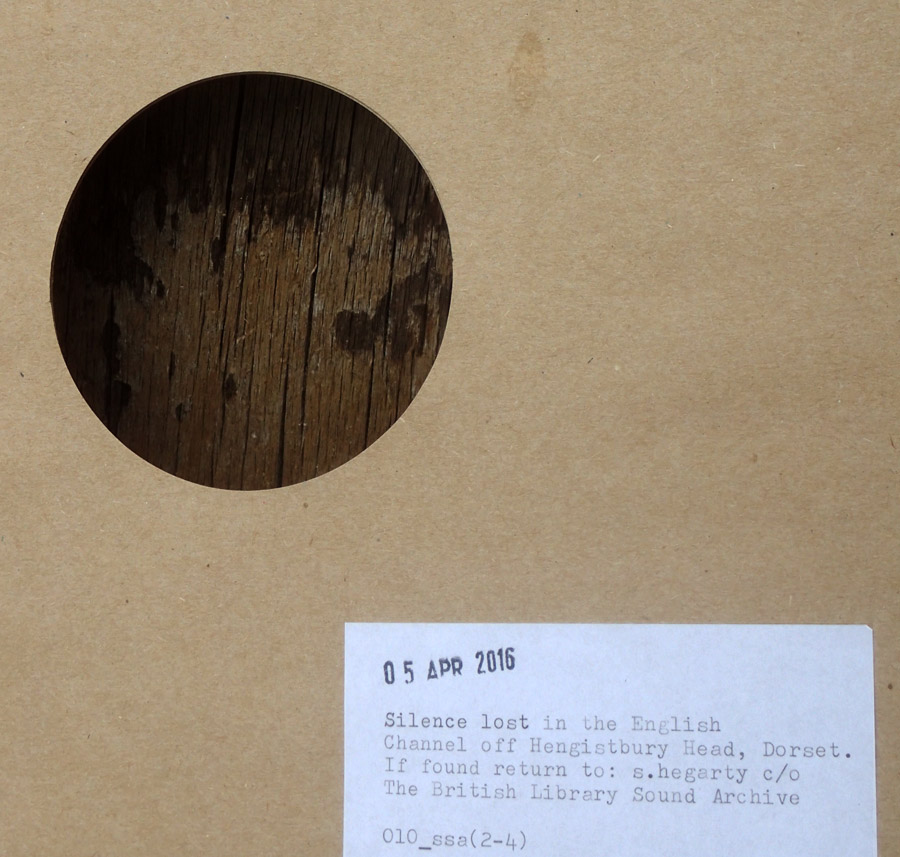

Since 2004, my sound practice has included a series of silent releases: unheard, unwritten works, sometimes performed, sometimes transmitted, often forgotten and occasionally lost. One of the most recent of these, Silence on Loan is an artists’ book, published in the form of a single-sided 10” vinyl record – although, cut with a silent groove, it is [not] a record of nothing.

The paper I presented at the conference, Silence on loan: Listening to silence and the unheard, draws on these silent works to explore silence as a potential and communal space: an act or situation of inaction which invites both listener and non-listener into unheard congress.

In a choreographed montage of words, voice, images, sound and silence, the paper was intended to include a performance of Silence on Loan. However, as part of the Artists’ Books Collection at Winchester School of Art Library, the book is catalogued as ‘reference only’. Therefore, although available to be handled and ‘used’ by library users, it cannot be removed from the library building. Thus confined, and magnetically protected from theft or ever being borrowed, Silence rests, jacketless on the library shelf, quietly gathering dust and harm, ‘waiting without waiting for’.

In conversation with the Head of Collections and curator of the Artists’ Book Collection at WSA, it was agreed that a retrospective contract, hastily signed and methodically duplicated, would permit myself: ‘free access to the artists’ book Silence on Loan on reasonable notice (1 month) being given […] and subject to standard loans procedures, for the purposes of performing it at exhibitions and /or events.’

Contract, dated, and signed, Silence was folded up in a shroud of acid free tissue and placed inside a grey archival box. With the passport of its paperwork enclosed, the book was issued, and silence was not only officially on loan, but also on tour. To commemorate, what is hoped to be the first in a series of ‘national’ performances, I created the official merchandise of a Silence on Tour badge, available free to all those attending.

Saying Nothing To Say was held in the Wolfson Research Exchange on the third floor of the library at the University of Warwick. As I entered the library, silence was heard to breach security, alarmingly announcing its presence as I passed through the magnetic surveillance of the library turnstile. A ceremony, embarrassingly repeated on exit.

With keynotes by Dr Maria Balaska (University of Hertfordshire) and Dr Thomas Gould, (University of East Anglia), the conference programme included panels on ‘The Missaid: at the limits of language’, ‘The silenced and politics of voice’ and ‘The unsaid’. Speakers included; Juulia Jaulimo (University of Helsinki/Justus Liebig University Geissen), who discussed ‘Kathy Acker, Samuel Beckett and the Poetics of Sous Rature’; Imogen Free (Kings College London) who explored the ‘thick almost guttural sound of the voice’ and resounding vocal relations in Rosamund Lehmann’s The Echoing Grove(1953); Owain Burrell (University of Warwick) who discussed ‘working-class’ silence in the parlour of Tony Harrison’s poems, whilst Jarkko Tanninen (University of Nottingham) focused on ‘Silence after Violence’ in the ‘photographic absence of Joel Sternfeld’s, On This Site.’

Details of the full program are available here.

Returning Silence on Loan to the shelf at WSA, required further papery exchange. A form, confirming that there had been ‘no change’ to the condition of the book was signed and duplicated. Silence was then carefully unfolded from its acid free shroud and slipped discreetly back between the hardbacks at 741.64 HEG.

Congratulations to Tabina Iqbal for organising such a fascinating conference and thank you to Tabina and Matthew Nicholas for making me so very welcome.