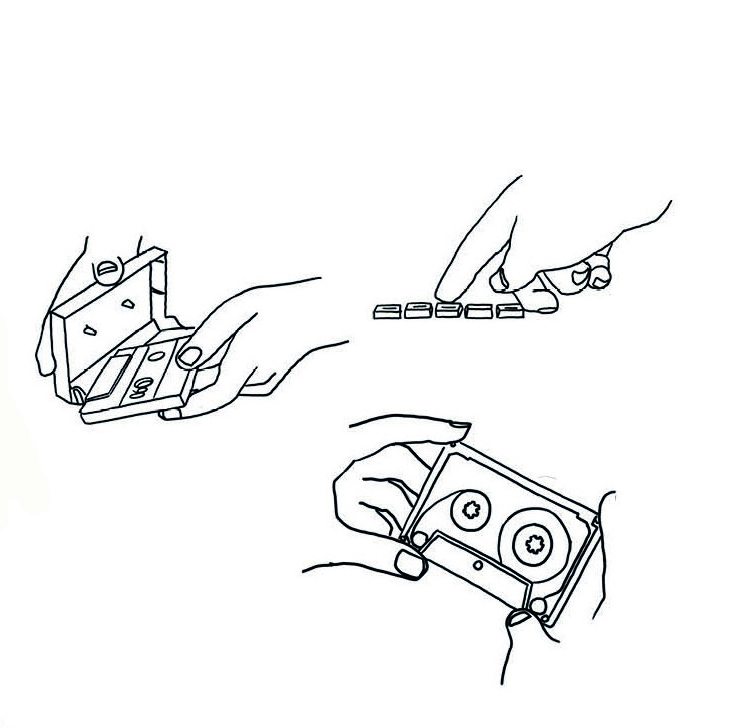

Fitting the cassette

To insert the cassette, push the cassette compartment button (8) in the direction of the arrow. The cassette compartment then opens. Insert the cassette with the full spool on the right, the empty spool on the left, then close the compartment door.

In the summer of ‘78, on the double-decked 500 bus from Lime Street to Kirkby terminus, Hilary slipped me a cassette. A C60 audiocassette.

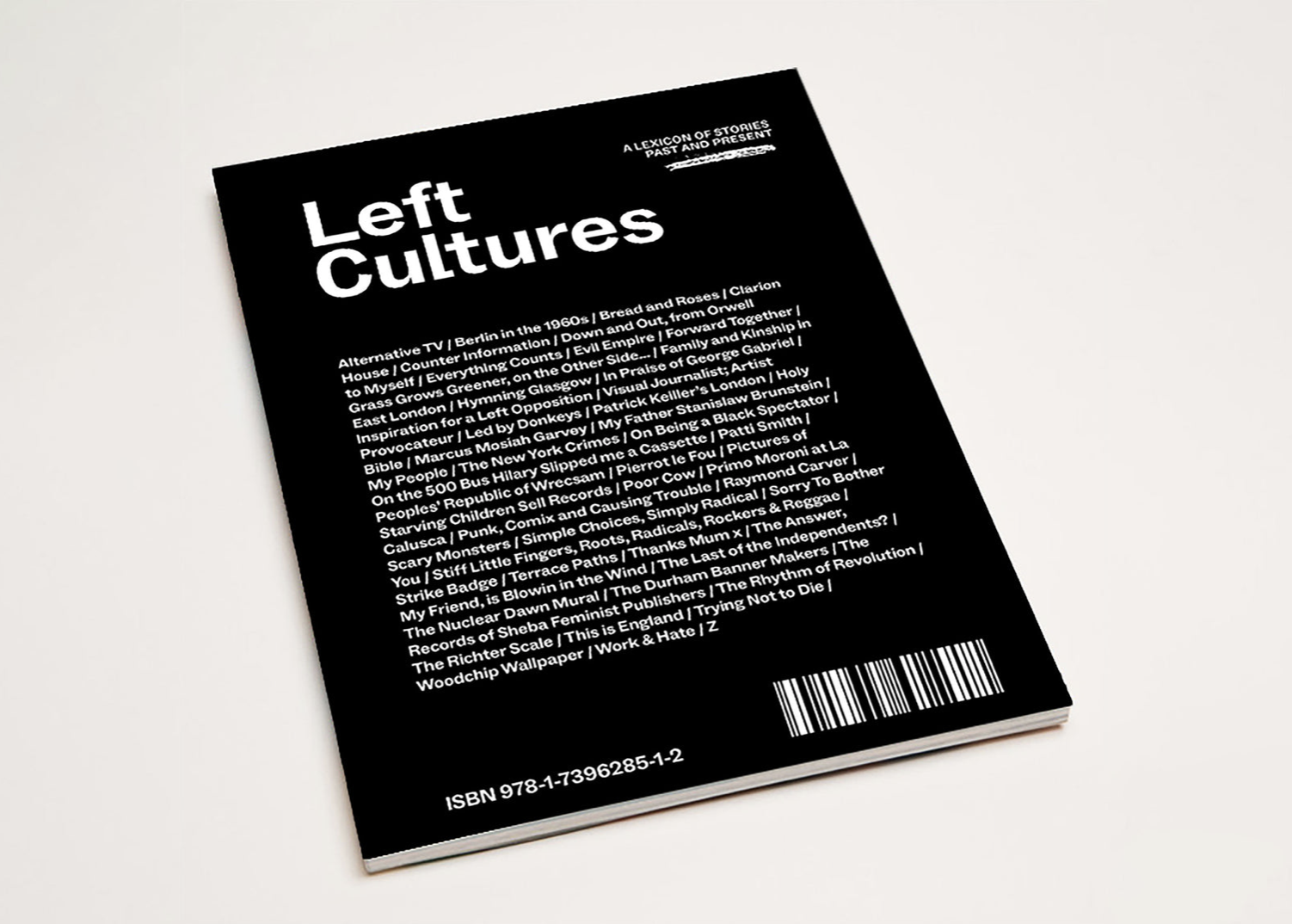

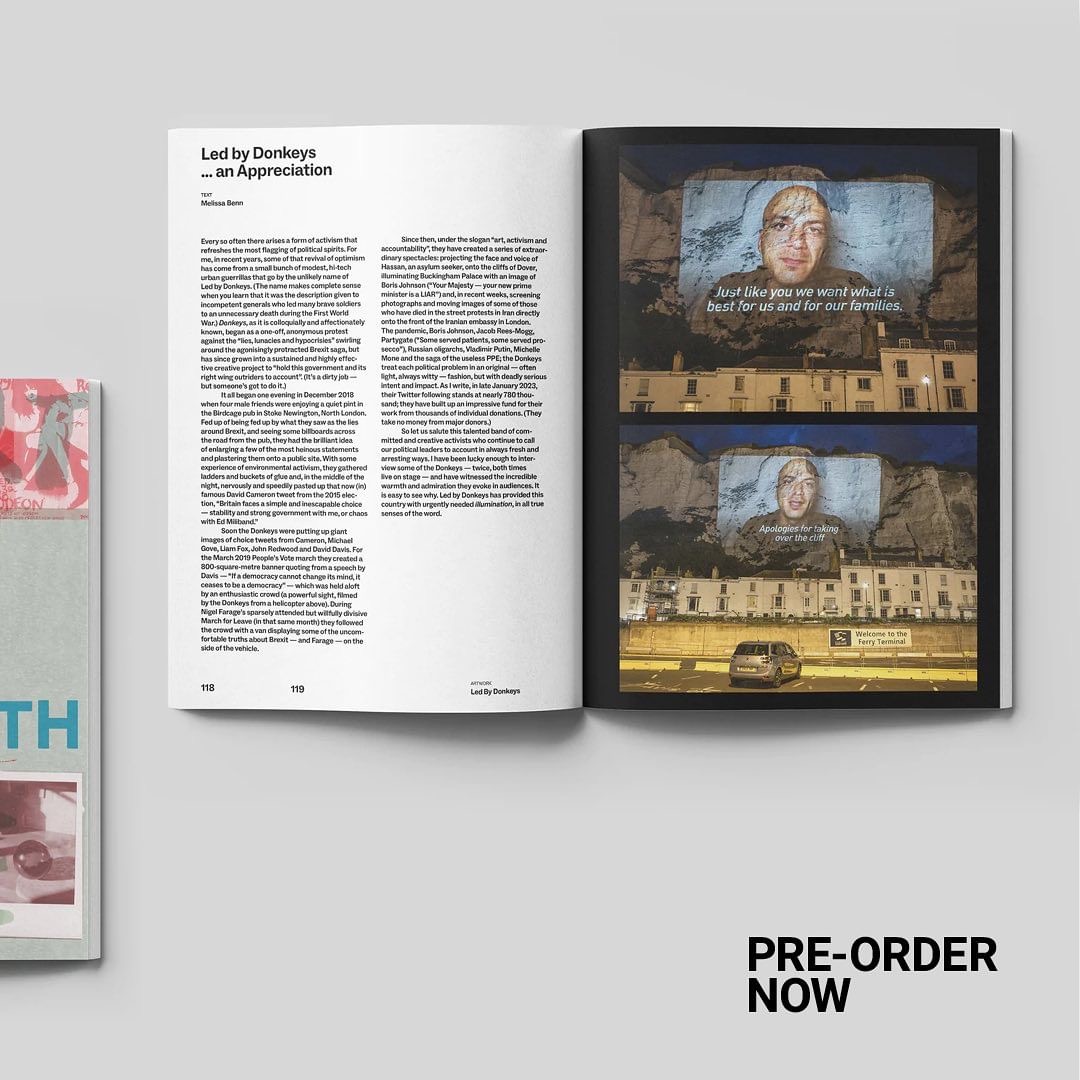

In 2022, some forty-five years later, I was contacted by Phil Wrigglesworth, Editor and Art Director of Left Cultures, who asked if I would be interested in contributing a ‘personal story’ for their next edition. Left Cultures is a unique publication, a contemporary space to champion all kinds of voices on the Left, publishing ‘other’ narratives, which are at once, culturally diverse, and left leaning.

I was delighted to be invited and excited to contribute.

This morning I awoke to the postal thud and seductive whiff of fresh ink on heavy matt paper: an advance copy of Left Cultures 2 had arrived. An exquisite ‘lexicon’ of left bent cultural stories, that smells good, feels good, and ‘fizzes’ with imagery, ideas, and energy: From the sartorial slogans of Johnny Hannah’s Crass inspired ‘pay no more than £3’ workwear, to Rachael Miles/Bessa unpicking the politics of woodchip and the Scary Monsters of David Beech’s scalpel splice through the counter-culture of Bowie’s lyrical landscapes and the artist-run organisational 'model’ of Punk.

Throughout the 50 stories and 128 pages, music appears a conspicuous and common agent of change. So too, my own story: On the 500 bus Hilary slipped me a cassette. But it’s not just the lyrics or energy of music that is important, it’s also the cultural exchange and community that forms through sharing and experiencing music.

The chance meeting of my encounter with Hilary, was spontaneously arranged through mass unemployment and the Youth Opportunity Programme (YOP). Hilary had been offered the career opportunity of becoming a part-time Library Assistant at my school, Brookfield Comprehensive in Kirkby, Knowsley, Nr. Liverpool. The library was small and impoverished with a predominantly disengaged clientele: as a career opportunity I am not sure Brookfield library knocked very loudly.

On her days off, Hilary (Steele) was more creatively [un]employed as a photographer for the Liverpool Punk scene around Eric’s; the nightclub where the Sex Pistols performed in ‘76. She was also friends with Liverpool’s proto-punk super group: Big in Japan (Jayne Casey, Holly Johnson, Budgie, Big Bill Drummond, Ian Broudie). In addition to the C60 cassette slipped into my hands on the 500, Hilary got me a signed copy of, From Y to Z and Never Again (Zoo, 1978), the posthumous extended play epitaph of Big in Japan. In a rare out of school meeting, Hilary took me to Probe Records where she tried to persuade Pete Burns to sell me a copy of Devo’s infamous bootleg, Workforce. Notorious for his acerbic approach to customer service, Pete of course, refused.

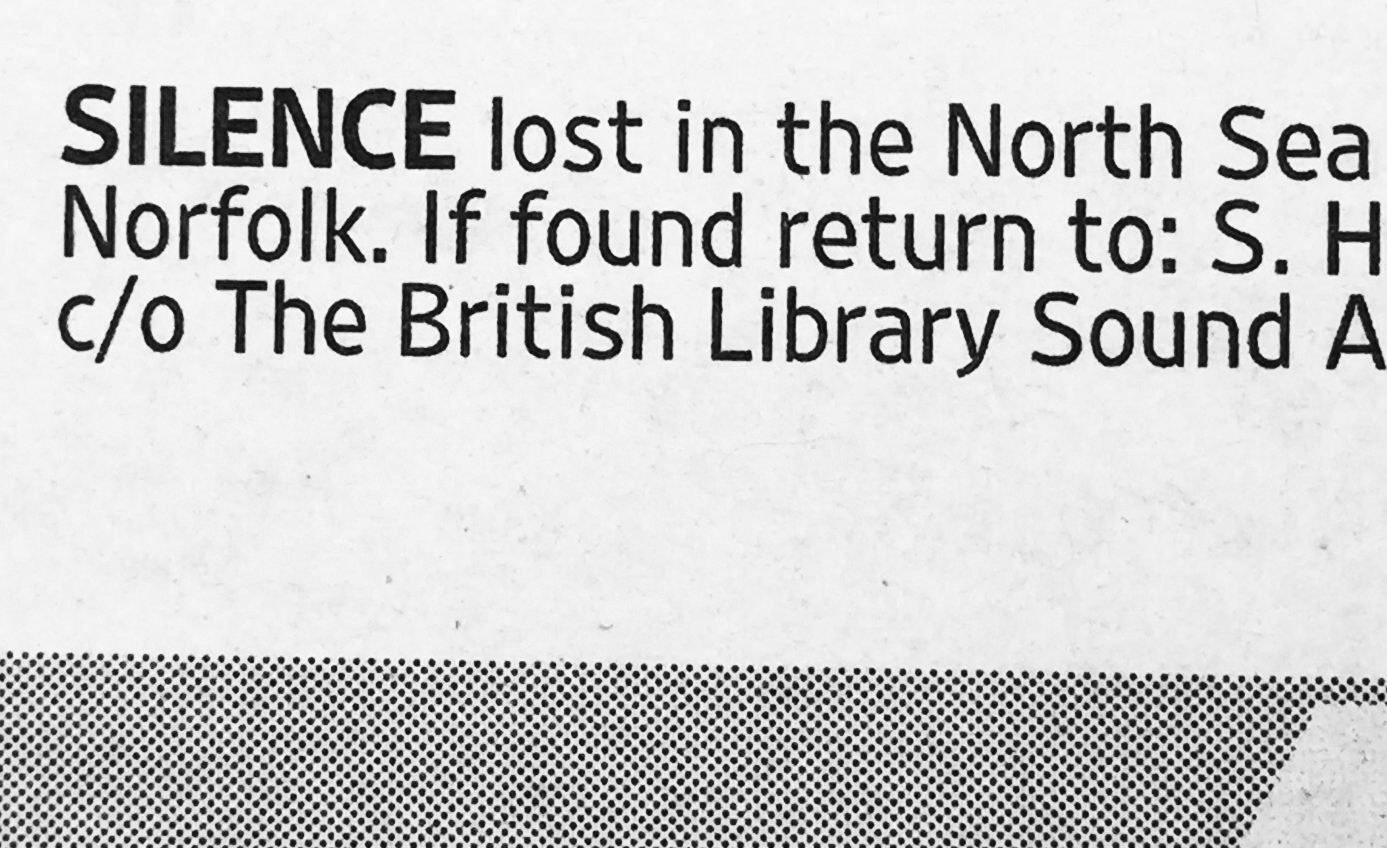

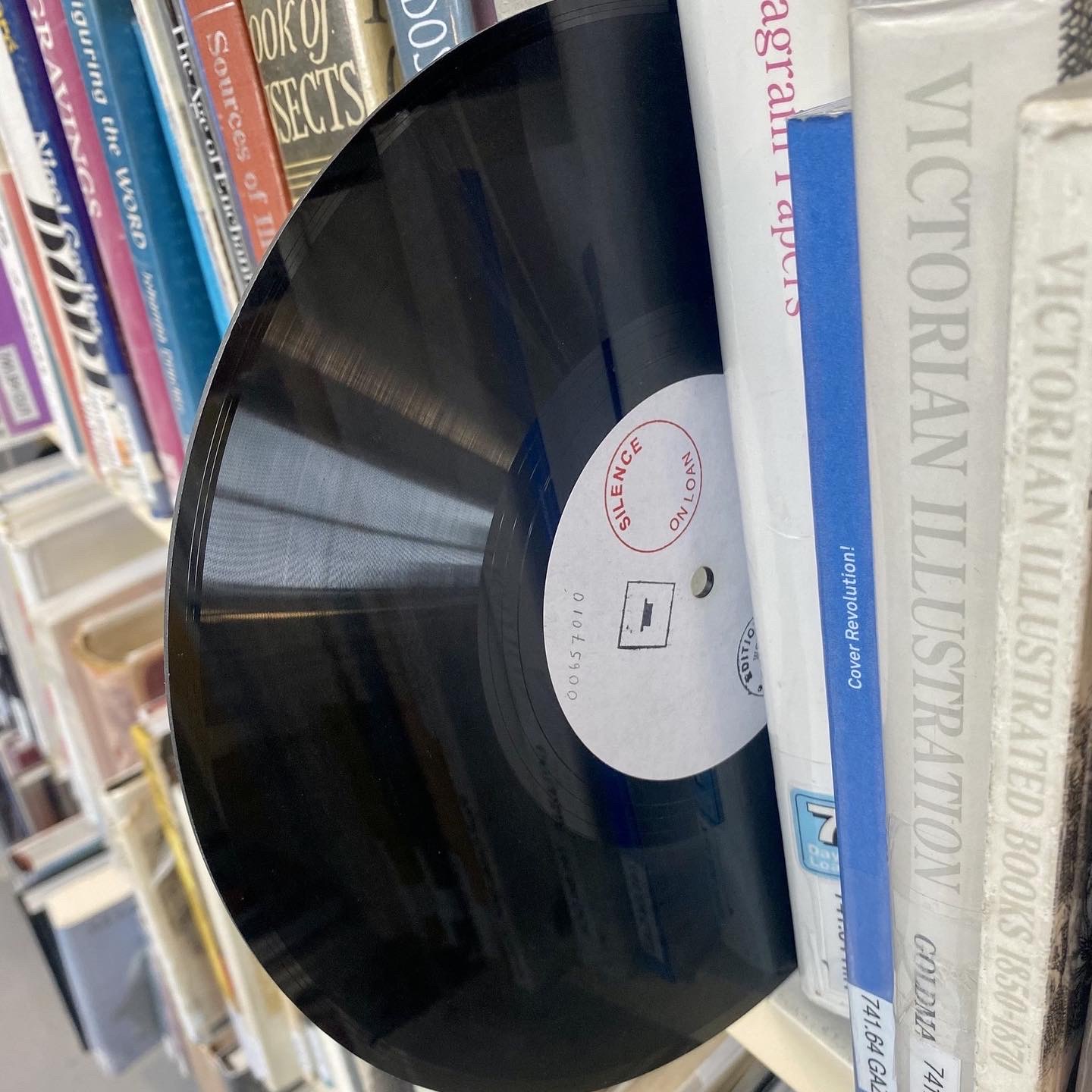

Record shops were critical spaces, where you had to earn the respect of the counter. Music was not easy to find or get, you had to listen out for it in the reviews and classifieds of the NME or discover it in the sleeve notes of other albums. There was of course the cultural antennas of John Peel and Phil Ross (Radio Merseyside), but it was the musical rumours of friends and the magnetic contraband of mixtapes that proffered an ear into the unknown.

The copyright infringing, ferric hour that Hilary took the time to curate and tape, spliced together the eponymous punk of Big in Japan, the Day-Glo dystopia of X-Ray Spex, the Handsworth Revolution of Steel Pulse and sparse, melancholy guitar of Link Wray & Robert Gordon’s cover of Fire. Gloriously eclectic Hilary’s mixtape wound my ear toward a music in which the personal mingled with the political.

C30 C60 C90 go

Off the radio I get constant flow

Hit it, pause it, record and play

Turn it, rewind and rub it away

C30, C60, C90 Go by Bow Wow Wow

(1980)

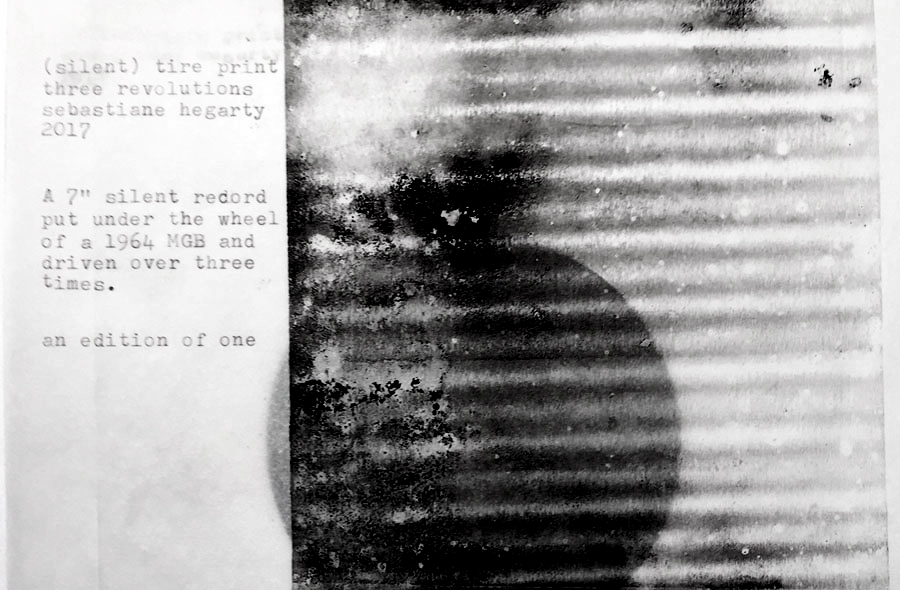

The audiocassette was a cheap, democratic and yet revolutionary medium. Through its ability to reproduce, rewind, mix, erase and share, we become the curators of our audible and erasable self. We could share, make and release music. At art school I set up a semi-fictional record label (Starving Panda Records) curating, duplicating and releasing, Sometimes the Tape Stops; a C90 compilation of sound and music made by friends and other students, many of whom formed bands, became musicians and sound artists for the duration of the tape and then split and retired back into painting, sculpture or ceramics. The audiocassette created a community, and a creative culture of sharing. You didn’t sell a mixtape; it was part of a gift economy, made to be shared, to be given away. We made tapes for friends, for people we loved, for people we left and those who left us. For people we met on the 500 bus

Hilary left the career opportunity of Brookfield Comp behind and I headed to Wolverhampton Poly to study Fine Art. I've searched, but sadly I can’t find Hilary’s cassette, but I did discover that a book of her photographs, The Crucial Years - Eric's Liverpool 1977-1979, was published by Hanging Around Books (Sadly sold out).

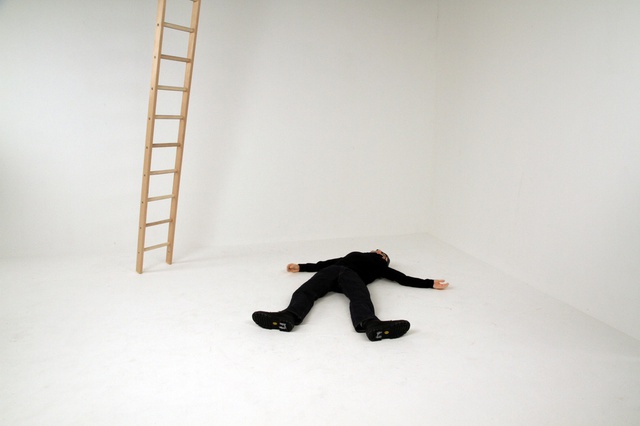

The tale of Hilary’s cassette, accompanied by the exquisite line of Colum Leith’s visual instructions is available in Left Cultures 2. You can order a copy here or purchase it in person at cool independent bookshops all over the UK.

Care of tapes

Please do not put your cassettes on top of central heating radiators or any other heat source. The tape will become deformed and useless.