On Friday the 31st January 2020, I arrived at Winchester School of Art Library to find a table ‘reserved for activity’. It had been one year and one day since Silence on Loan was added to the Artists’ Book Collection at the WSA Library. Held without the protection of cover or sleeve the book (a single-sided 10” dubplate cut with a silent groove) is shelved at 741.64 HEG. Wedged between the hardbacks, this mute slither of vinyl is easily overlooked, but once a year it is taken from the shelf and placed on the platter of a portable turntable. [Re]turning at thirty-three and a third revolutions per minute the dubplate slowly pronounces the dust and harm that has come to its surface: the silence that has been lost. Once played the silence is put back on the shelf, where it is left un-sounding for another year.

As a performance, this annual audition is rather disappointing; nothing much happens for slightly more than nine-minutes. Those who are here to hear (and those library visitors who’s listening the silence loans) listen to silence being broken and unheard. Perhaps the tables are turned, and it is the listeners who perform the silence rather than the record player’s stylus. For many of those who came, this is a return to silence, having been here last year when Silence on Loan was performed at the moment of its inclusion into library stock. Just as the dust collects in the groove, so silence returns and gathers in the ear of those who come to listen and remember listening again.

Everyone who is, and now was, there to hear, receives a souvenir in the form of a Silence on Loan 2020 pin-badge, whilst a paper wristband and UV hand-stamp, temporarily confirm admission and attendance.

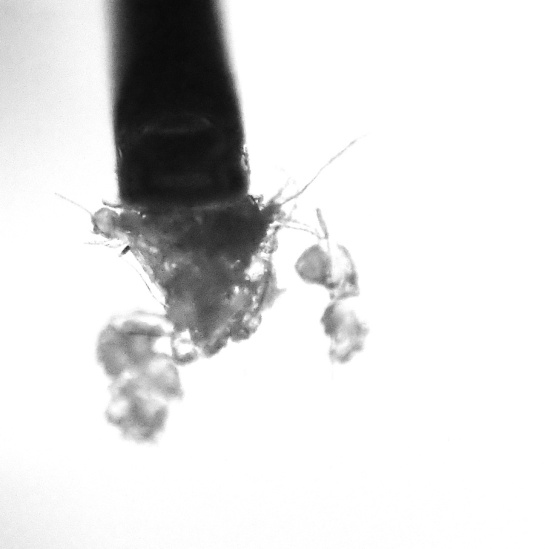

I had been inclined to record each performance, so that I might document and measure the changes that time brings to the silence. But such calculating permanence would surely imprison that which does not sound, that which is fragile, fugitive and evasive. Silence, is more concerned with the potential for sound than its absence, most [in]audible when we imagine what we don’t hear. The analogue frailty of a physical recording can be used to augment this un-sounding potentiality. The performance on the 31st was documented using an old portable audio cassette recorder. Such obsolete media is characterised by a distinct lack of [hi] fidelity, recording its own imperfections and imposing its own magnetic patina upon the sound it records. This failure to create a faithful document is enhanced by the recording not being monitored – the tape can be seen slowly winding from left to right, but no lights or needles visibly meter the units of volume.

The quantity of tape used measures the duration of silence recorded, transcribing [no] sound into a spatial length, but the cassette is never played, and the silence remains unheard. Paused at this distance, the silence waits next year’s anniversary, when it will be re-wound and next year’s silence recorded over this. An [un] sounding and unfaithful record, this audio document, simultaneously returns and erases the silence of another year.

The next performance of Silence on Loan will be in January 2021